History of Clapham Common

(extracted from 2007 Masterplan)

Introduction

The following is a summary history assembled from published sources and drawing on recent work on the Common by the Clapham Society and the Oxford Archaeological Unit, plus advice from Michael Green (a local resident with a profesional interest in the Common’s history).

Early history

Clapham Common lies on the third gravel terrace of the Thames, implying that the area was well drained and suitable for cultivation and settlement during the Prehistoric period. However it has been suggested that the gravels in the area were eroded at some time between the Pleistocene and later Prehistoric period resulting in water retention and creating a marshy landscape with small streams, pools and boggy areas. The timing of the erosion is unclear at present leaving in doubt the presence and nature of Prehistoric settlement or other activity on the Common. The level of Roman activity is also unclear although a major Roman route, Stane Street, is nearby.

The Medieval Common

By the late Saxon period the Common was known as Grendel’s Mere and this association with Grendel, a mythical creature who lived in a pool, indicates the boggy nature of the ground. At this time it is likely that the Common would have been used for gathering fuel and wild plants for food. Clapham is recorded as Clopeham in the Domesday Survey of 1086. The area was Common Land throughout the later medieval period (probably since before the Norman Conquest). This allowed Commoners rights to graze animals, collect fruits, wood and furze (a gorse like plant used for fuel) and for drying washing. They could also use a spring and had rights to a windmill for threshing grain. The presence of ‘lazy beds’ near the bandstand indicates that some sections of the Common were brought into cultivation during times of land shortage, in particular in the 13th century. Clapham Common has historically been divided between the manors of Clapham and Battersea and during the rise in population in the 15th century the need for fuel

gathered from the Common lead to tension between the two lordships. During the Civil War the Lord of Battersea supported the King while the Lord of Clapham supported Parliament. This may have worsened relations between the Commoners of the two parishes and in 1716 the Battersea Parishioners dug a ditch across the Common to deny the Clapham Commoners their rights. The ditch was along the line of a Saxo-Norman boundary feature (possible already taking the form of a ditch) which later became the parish boundary and is still visible as a cropmark mainly to the south of the Bandstand. The Clapham side took the case to law and won and the ditch was backfilled.

The 18th Century

During the 18th century the areas immediately around the Common changed from largely rural fields to become the sites for villas for rich merchants who required large country houses in easy reach of the City. At the beginning of the century the Common was still overgrown and boggy with scattered trees and copses. A commentator notes in 1828 that during the last century the Common was “little more than a morass and the roads over it were almost impassable” and Thomas Mattox described it in 1719 as “being full of bushes and brambles, and shrubbed oaks”. The new, more prosperous, local residents began to modify the Common by planting trees, draining and levelling areas and improving some of the ponds. In 1722 a local magistrate Charles Baldwin began maintenance work partly from his own funds and partly by public subscription. By 1760 the Common was said to be “well planted with trees of various species”.

The Common was quarried for gravel, with Mount Pond originating as a gravel pit dug in 1746 to provide material for the Turnpike Road to Tooting. The use of the Common as a source for firewood, water, pasture and as a drying field continued alongside improvements and incursions by the new residents such as Mr Henton Brown who built a bridge to the island in Mount Pond and created a summer house in the form of a pagoda on the Mount. In 1776 the Holy Trinity Church was built in the north east corner of the Common. A committee had been set up a few years earlier to defend the Common from encroachment. They also planted broom and ornamental trees including elms around Holy Trinity Church. The Common also provided a site for exercise and popular entertainment with archery (from the early 17th century), horse racing (1674 onwards), riding along the turf gallop (now the Avenue), fairs and boxing matches.

19th century (leisure use) At the beginning of the 19th century local residents enjoyed the still slightly wild nature of the Common including the historian Thomas Macaulay (1800-1859) who as a boy (according to his biographer George Trevelyan) “use to roam that delightful wilderness of gorse bushes and poplar groves which was… a region of inexhaustible romance and mystery… A slight ridge, intersected by deep ditches, towards the west of the Common, the very existence of which no one above eight years old would notice, was dignified with the title of the Alps”. This does not refer to the current area between Mount Pond and Battersea Woods, also known as the Alps, which is of recent origin.

A collection of sketches and prints by Joseph Powell (1776-1840) dating from 1818 to 1823 give a glimpse of the Common in the early 19th century. Sketches of the area around Holy Trinity Church and the Pavement show a dense path network (much of which survives today), smooth grassland and lines of trees around the church and at the edge of the Common. In one view a coach and man on horseback traverse Long Road, people stroll along the paths, cattle and sheep graze, and already a lampstand is in place by a path. Post and rail fencing defines the edge of the Common and bollards mark the intersections of routes.

Other sketches show the rougher, more varied topography and ground cover of the main body of the Common. A view to the north east of the common shows rough terrain (probably due to gravel quarrying) with low heathy vegetation, with a line of washing strung between trees and, in the background, a grand mansion with wooded grounds. Mount Pond is shown backed by groves of young trees, and horses and donkeys grazing and drinking from the pond.

In many of the views there are people walking or enjoying sitting at ease on the Common however it seems that by 1836 there was public feeling that the site required improvement. A committee was formed and raised £7,000 for draining and filling up disused gravel pits and making a cricket pitch. In the 1820s there were ten ponds on the Common, this was reduced to seven by 1870 and to the current pattern of four (including Cock Pond – now the paddling pool) by 1895. As the 19th century progressed mass transport allowed people from further afield to visit Clapham Common, via trams in the latter half of the century and, from the turn of the century by tube. During the late 1800s the surrounding area was also changing radically with speculative builders creating terraced housing on the sites of many of the grand houses that fringed the Common. Sport and popular entertainment had been established on the Common for many years but sport in particular became more prominent and varied with the increase in visitors and local residential population. Cricket had been played on the Common since the 18th century, football was also played and reached a high point in 1880 when Clapham Rovers won the FA Cup. The Clapham Golf Club was established on the Common in 1873 (the 2nd oldest in London) and play continued (albeit restricted to early mornings) until conversion of the course to allotments in 1939. Sailing model boats on the Long Pond began in the 1870s making the site London’s oldest model yachting site. In 1877 Clapham Common was acquired by the Metropolitan Board of Works and was granted as open space for public use for ever. The Board of Works had powers to improve the landscape and Committee Minutes from 1877 refer to resolutions to provide facilities including a portion for horse riding to be defined “by trees and short lengths of fencing”. This seems likely to be the present planting along the Avenue which is shown in place on the OS map of 1895. The major changes to the landscape made by the Metropolitan Board of Works are shown in the differences between the OS maps of 1870 and 1895. In the earlier map the Common is largely informal open space crossed mainly east to west by minor paths. There are scattered trees and much of the west of the Common is rough or heathy ground.

In 1889 responsibility for the Common passed to the London County Council (LCC) and by 1895 a more formal park-like layout has been imposed centred on the Bandstand with radiating paths and a formal avenues of trees along the Avenue. The Bandstand was installed in 1890 and is now the largest and best surviving example of a Victorian Bandstand, it has recently been restored with funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, along with its immediate environs and the nearby Refreshment House. Another landmark, the temperance drinking fountain was moved from London Bridge to the Old Town section of the Common in 1895. Despite these more formal elements grazing animals on the Common continued into the early 1900s.

20th century (wartime changes)

The Common underwent dramatic changes during the 20th century mainly due to activities during the two World Wars, these further reduced the topographic variety and natural vegetation of the Common leading on to its intensified use for sports during the latter part of the century. During World War I much of the Common was given over to allotments with 150 people allocated a total of 12 acres within an hour of the outbreak of war.

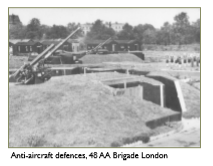

Other activities included the creation of a practice trench system in the north west quarter of the Common. The Second World War also required the conversion of the land to allotments and almost all of the Common was given over to food production at some time. The only sections not affected were immediately to the north and south of the Bandstand. An anti-aircraft battery was sited on the Common along with a radar post and prefabricated buildings were put up nearby along with some along Rookery Road which were not removed until the 1950s.

Pit alignments at the north east of the Common are likely to have been World War II anti-glider defences. Between 1940 and 1942 the deep shelter was built at Clapham South Underground Station. It was not until 1948 that all the requisitioned land was released by the War Office to the control of the LCC. The use of the Common for allotments destroyed most of the remaining rough heathland character, levelling the site and increasing fertility so that vigorous grass species became dominant almost completely replacing the acid grassland species.

Following the end of the Second World War the Common returned to its function as a venue for public entertainment, with the LCC providing outdoor ballet, theatre and boxing matches. Popular horse shows were held from 1954 to 1985. In 1965 the responsibility for the Common passed to the Greater London Council (GLC). In 1971 ownership and management of Clapham Common was vested in the London Borough of Lambeth as part of the dispersal of the GLC’s open spaces to the boroughs.

In 1987 the great storm brought down 200 mature trees and damaged 400. These have not been fully replaced despite the fund-raising efforts of the Clapham Society (formed 1963). Further developments were the new “Alps” close to Mount Pond, and the addition of cycle paths. In 1996 the Clapham Common Management Advisory Committee was formed and in 1998 the Friends of Clapham Common came into being.